The campaign ahead of the 2023 parliamentary elections lasted more than two years, deeply dividing Polish society and mobilising a record number of voters on the final straight. The ruling nationalist populists of the Law and Justice party (PiS) overstepped many boundaries, only to be finally punished by a majority of citizens.

In Poland, the election campaign officially begins when the president announces the election date. This year, Andrzej Duda did so during the summer holidays, on 8 August. A few days later, the Sejm, in which the PiS had a parliamentary majority, passed a resolution to also organise a nationwide referendum on election day. Practically, however, the election campaign had started two years earlier, with the return of Donald Tusk to national politics. Once again, age-old opponents clashed in the political ring: Tusk as leader of the liberal-conservative Civic Platform, which has been the largest opposition party for the past eight years, and Jarosław Kaczyński as leader of the nationalist and populist Law and Justice party, in power since 2015. Both, by setting and controlling the axis of political conflict, were able to generate and maintain internal cohesion not only within their political parties but also within antagonised groups of voters, seeking to marginalise all other formations, such as the New Left, the agrarian Polish People’s Party (then labelled the Third Way), or the far-right Confederation.

Campaign dynamics and game changers

The stakes of this election were high, although different for the opposition and for Law and Justice. The ruling party had failed for eight years to finalise its retreat from liberal democracy towards building a ‘sovereign democracy’, so it fought for a third term to subjugate the judiciary and abolish the independence of judges, eliminate the plurality of private media, make the non-governmental sector fully dependent on the state, and minimise the powers and finances of local authorities. Under the pretext of following the will of the ‘sovereign’ (that’s what PiS called citizens) expressed in the 2015 and 2019 elections, the ruling party has also fought the European Union, the most important actor with the tools to curb the authoritarian inclinations of a member state. The aims of the entire opposition, the Civic Coalition, the New Left, the Third Way, were to prevent the demolition of the rule of law, to normalise relations with the European Union, to stop the process of state capture, the colonisation of the public media and the destruction of all entities that could not be subordinated to PiS.

Despite such high stakes, the campaign run by those in power was often grotesque. For example, it used public television and social media to try to make the public believe that the European Union wants to force Poles to eat worms and ban them from eating meat, or that in the name of reducing consumption, the European Commission will issue a ban on buying new clothes and impose limits on car ownership per household. The entire PiS campaign focused on opposition leader Donald Tusk, who was portrayed as the devil, simultaneously an agent of Germany and Russia, a traitor who fled domestic problems in 2014 to take a lucrative job as president of the European Council and returned to Poland in 2021 only to harm the country.

The Civic Coalition, on the other hand, completely personalised its campaign, which had Tusk’s face. He toured the country for months, speaking at open meetings with voters, and campaigning directly. The first turning point of the campaign was a call for citizens to protest in the capital on 4 June of this year against government policies, inflation and high prices. The turnout at the demonstration was paradoxically boosted by President Duda, who a few days before that date signed a law allowing the elimination of the opposition leader from politics under the pretext of shady contacts with Russia.

Buoyed by the turnout success, Tusk organised a second demonstration in Warsaw on 1 October, two weeks before the elections. The mobilisation was huge, with about a million citizens walking the streets of the capital, not only supporters of one party, but the entire opposition. Its leaders, incidentally, appeared alongside Tusk, calling for participation in the elections.

Rule-bending by the ruling party

Lacking such mobilisation capacities as the opposition, the ruling party used state resources without inhibition, violating the principle of equality and fairness in elections. While it was legal for Law and Justice campaign contributions to be made by people employed by state-owned companies thanks to their connections to the ruling party, it is difficult not to consider them a sign of political corruption. The Law and Justice party used – as in previous campaigns – public media for crude propaganda and attacks on the opposition. Local newspapers, bought out a few years ago by the state oil company Orlen, refused to allow the opposition to place paid election ads. To further increase its financial advantage, PiS, through its parliamentary majority, organised a nationwide referendum with biased questions and that implied untruthful claims, such as the forced relocation of immigrants in the EU. The referendum was intended not only to harden the PiS electorate, but more importantly to allow public money to be spent unchecked by the State Election Commission during the election campaign.

The response of citizens has been spectacular. A few weeks before the election, women, especially young women, declared that they were hesitant to vote at all. The feeling of powerlessness when confronted with the ruling party, which has imposed a total ban on abortion and failed to respond to the huge street protests of 2020, had translated into general disillusionment with politics. However, even more women than men attended the polls on election day. Frustration turned into action. There was also a huge mobilisation of Poles living abroad, similar to that of 2007, when it already had succeeded in ousting PiS from power in Poland. Opposition voters in the country practised large-scale ‘electoral tourism’: they changed their electoral district to one where their vote carried more weight than in big cities. The popular movement to the polls ultimately translated not only into record turn-out, but, most importantly, an electoral result that allows the parties until now in opposition to begin negotiations to form a government coalition.

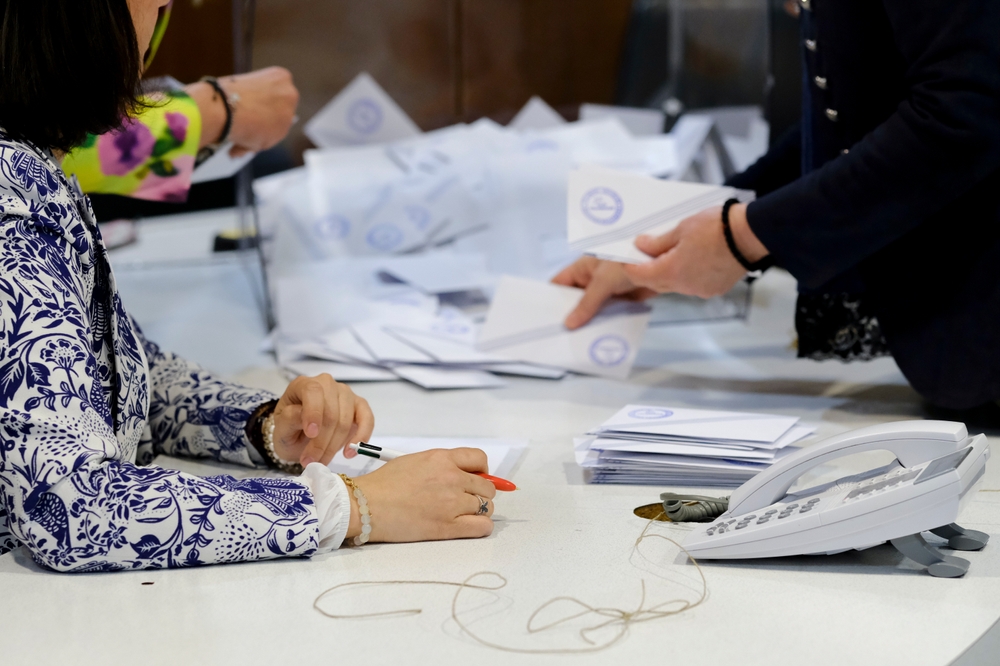

Photo credits: Shutterstock.com/Lukasz Michalczyk